2.4 Multi-attention head

Building a multiple context-specific representations of a token.

Diagram 2.4.0: The Transformer, Vaswani et al. (2017)

Extrapolating single-head to multi-head

The multi-head attention layer works largely similarly to a single self-attention as above, but the multiple instances of the heads mean that there are multiple instances of the WQ, WK, WV matrices, such that the weights within each set of (WQ, WK, WV) possess different focuses.

For example, one self-attention head, and therefore one set of (WQ, WK, WV)1 may be oriented around finding grammatical relations between tokens, whilst a different head with a different set of weights (WQ, WK, WV)2 may focus on finding tense-based relations between tokens, whilst a different head with a third unique set (WQ, WK, WV)3 may focus on syntactic relations between tokens. Finally, the results of each single attention-head are concatenated, as in akin to string concatenation, and due to the dimensionality change are then multiplied by a matrix WO to return the vectors back to the original dimensionality.

Transformers are typically trained end-to-end (all layers trained at once)[1], using specific word-oriented problems. Before training, the weights within the matrices of a self-attention head - WQ, WK, WV - are all initialised at random, then specific training tasks and loss functions are used to refine all weights within the model, including the weights within each self-attention mechanism. Examples of loss functions may be to fill in the blank within a sentence, or to detect out-of-place tokens (after corrupting sentences via an automated method).[2] Because the loss functions are so oriented only on producing the expected output, it is possible that, as with vector embeddings generated via neural networks, that the actual relations that (WQ, WK, WV)i represent have never been formally defined by humans.

Orienting self-attention to hardware

Diagram 2.4.1: An example of how all the weight matrices of 1 self-attention head can fit within 1 GPU tile, where each input vector is of 20 bytes (e.g. 10 dimensions when using bfloat16, or 20 dimensions for 8-bit integers), and a tile is 64x32 bytes. A GPU is oriented around operating on tiles, and can run matrix multiplication on multiple tiles, simultaneously. Consider that there may be multiple instances of the weights tile, each with a different set of weights, one per self-attention head.

In the original Transformer, 8 attention heads were deployed,[3] meanwhile Llama-4’s default configuration is for 32. In the context of space constraints, a single attention-head can be reduced in dimensionality, so as to allow for multiple attention-heads of smaller dimension. In this sense, modern GPUs which (currently, as of 2025) most energy-efficiently handle matrices of tile size 128x256[4], are able to derive attention scores for one input sequence across multiple heads, simultaneously.

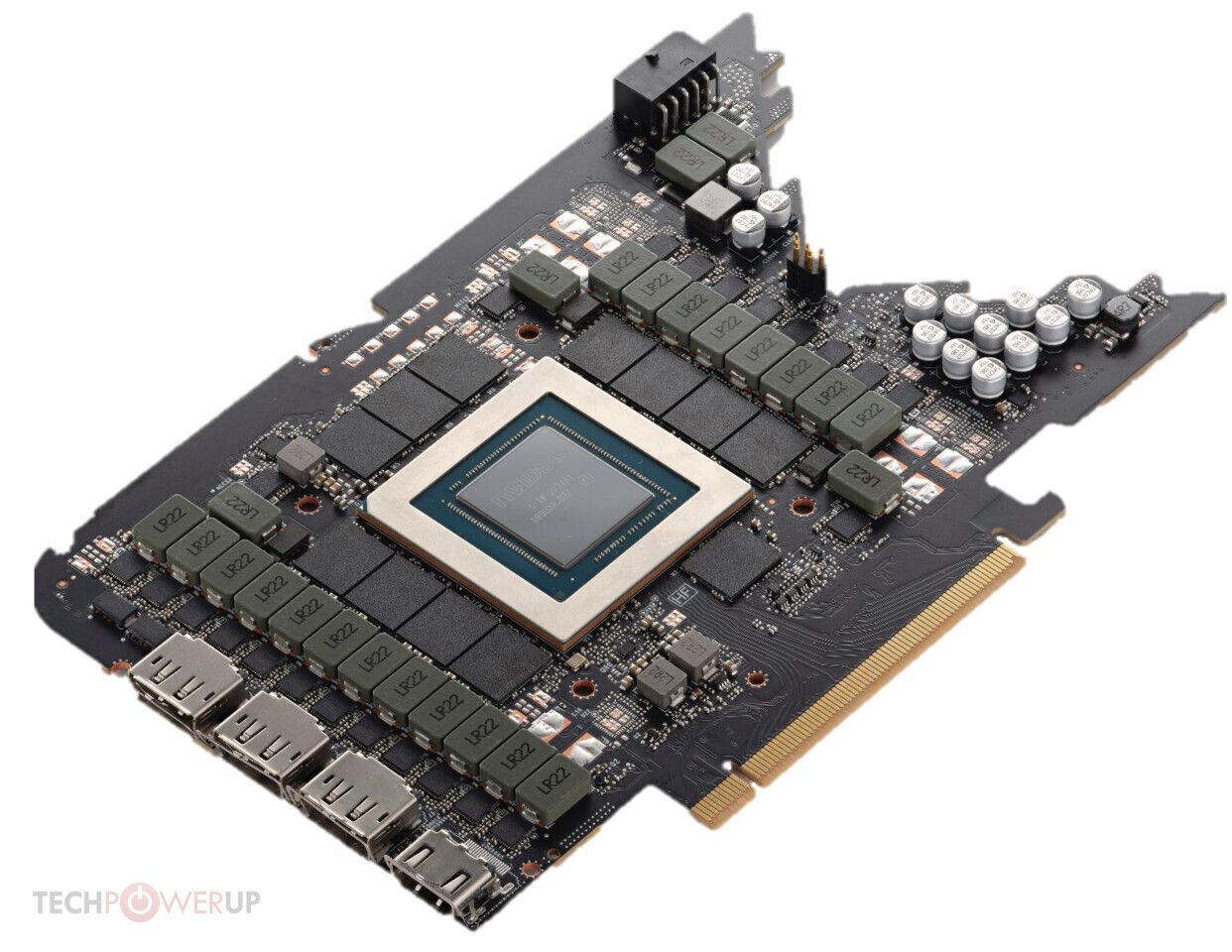

Diagram 2.4.2: A GPU (SIMD processor), without cooling features.

Consider how abstract and incomprehensible the output of a self-attention head is; this is the experimental end of mainstream computer science. This level of abstraction is also a large critique of LLMs generally - difficult to comprehend, therefore difficult to fix when something goes wrong. Significant effort must be put into engineering sanity checks, but this topic is a whole separate chapter in LLM textbooks. For this reason, this online textbook will no longer be looking at explicit/numerical matrices.

References

[1] Training a causal language model from scratch - HuggingFace [2] Large Language Models: A Deep Dive, Chapter 2.5 [3] Attention Is All You Need, 3.2.2 [4] Matrix Multiplication Background User’s Guide